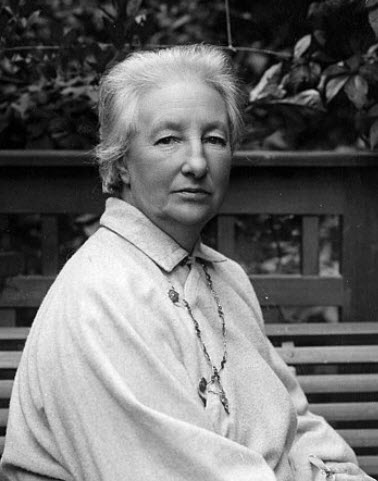

Anita Augspurg (1857-1943) was a German jurist, actress, and writer. As a political activist, she was pro feminism and pacifism and against nazism, antisemitism and colonialism.

Anita Augspurg (1857-1943) was a German jurist, actress, and writer. As a political activist, she was pro feminism and pacifism and against nazism, antisemitism and colonialism.

Allthough born and raised in Germany, Augspurg moved to Switzerland to study law at the university in Zürich since women in Germany did not have equal access to universities.

In 1897, Augspurg earned her doctorate and became a doctor of law of the German Empire – but she still couldn’t practise as a lawyer in Germany since women were not allowed to do so. It wasn’t until 1922 that women with a JD were allowed to practise law in Germany.

Short facts about Anita Augspurg

| Born | 22 September 1857 in Verden, Germany |

| Died | 20 December 1943 in Zürich, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Lawyer

Actress Writer Political activist |

| Nationality | German |

Early life

Anita Augspurg was born in 1857 in Verden, in Lower Saxony, Germany. Her father was a lawyer, and during her adolescence Augspurg worked in his law office.

Studies in Berlin

After reaching the age of majority, Augspurg completed a teacher training course in Berlin that qualified her for working as a teacher at women’s colleges. While in Berlin, she also took acting classes.

Acting

In 1881, the 24 year old Augspurg joined the Meininge Ensemble as an apprentice. The Meiningen Ensemble was the court theatre patroned by Georg II, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen. (He enjoyed theatre so much he became known as the Theaterherzog – the theatre duke.) The ensamble toured Germany and Europe and became famous for its historically accurate stage settings and high quality performances.

Augspurb toured with the ensemble in 1881 and 1882, particpating in concerts across Germany as well as in Lithuania and the Netherlands.

In total, Augspurg would have a five year long career as an actress.

Inheritance

In 1887, Augspurgs maternal grandmother died, leaving her granddaughter a larger inheritance. This made Augspurg financially independent.

Photography

After inheriting money from her grandmother, Augspurg left the stage to open a photography studio in Munich together with Sophia Goudstikker, whome she had befriended as Goudstikker was attending an art school in Dresden which was directed by Augspurg′s sister.

The photo studio, named Hofatelier Elvira, opened in 1887 and (Dutch-bord) Goudstikker became the first unmarried German woman to obtain a royal license for photography. Augspurg and Goudstikker recieved a lot of attention – and criticism – due to their unconventional lifestyle. They ran a business, they dressed differently, they wore their hair short and they vocied their support for women’s liberation. A few years after opening Hofatelier Elvira, Augspurg had turned into a strong force within the women’s movement in Germany and a skilled public speaker.

The studio flurished side by side with the two owners’ political involvement, with anyone from the Bavarian royal family to artists and intellecturals having their photographs taken there. This was partly due to the many valuable contacts that Augspurg had made during her career as an actress. In addition to being a photo studio, Hofatelier Elvira developed into a meeting place for the avant-garde, frequented by personalities such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Isadora Duncan and Marie-Adélaïde, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg.

In 1889, Augspurg and Goudstikker joined the German Women for Reform, a movement working to remove laws that prohibited women from attending university in Germany. Soon, the two women were also members of the Modern Life Society. Both societies were kept under police surviellance since they breached the ban on women’s political involvment. In 1894, the two women participated in the creation of a new group: Vereins für Fraeninteressen (Society for Women’s Interests).

In 1898, the partnership between Augspurg and Goudstikker was dissolved and Goudstikker took over the studio, which she ran until 1908.

Law

Augspurg involment in the women’s movement encouraged her to obtain a law degree, but doing so in Germany was not possible since she was a women. In Switzerland, the laws for female students were different, so Augspurg studied law at the University of Zürich.

A staunch supporter of women’s right to education, Augspurg participated in the creation of Internationaler Studentinnenverein (The Internatinoal Female Students Association).

Augspurg earned her doctorate in 1897, becoming a doctor of law of the German Empire. Despite this, she could not practise law in Germany since this was not permitted for women regardless of their formal qualifications.

Even before obtaining her doctorate, Augspurg had began writing articles for the newspaper Die Frauenbewegung (The Women’s Movement) where she criticised the legal discriminaction of women, especially when it came to marriage law. In 1896, she attended the International Conference of Women in Berlin, and this is where she got to know the German feminist activist Lida Gustava Heymann who would become her partner for the rest of her life.

More political activism

By the turn of the century, Augspurg was focusing her attention on promoting a change of the German Civil Code, especially concering marriage law and family law. In this, she worked closely with Marie Raschke and Minna Cauer.

In 1902, Augspurg was one of the founders of an association for women’s suffrage in Hamburg.

In 1905, Augspurg’s “Open Letter” was published, where she argued for a radical change of the German marriage law.

In 1913, Augspurg was one of the founders of an association for women’s suffrage in Bavaria.

First World War

During the First World War, Augspurg and Heymann used their home in Munich to organize illegal gatherings of political activists. In 1915, they travelled to the Netherlands to participate in the International Congress of Women in The Hague.

Between the wars

After the proclamation of the Wiemar Republic in 1918, Augspurg became a member of the provisional Landtag of Bavaria.

In 1919, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedome was formed. Heymann became its vice president and Augspurg was also heavily involved in the organisation.

In 1922, a new euality legislation enacted by the Weimar Republic removed the ban against women practising law. Now, Augspurg was finally legally permitted to practise law in her homeland.

In 1923, Augspurg and Heymann appealed to the Bavarian Interior Minister, urging him to expell the Austrian Adolf Hitler on grounds of sedition. The Bavarian government did attempt to have Hitler deported to Austria while he was serving a sentence in Landsberg Prison, but the Austrian federal chancellor refused to recieve Hitler on the specious grounds that Hitler’s service in the German Army during WWI had made his Austrian citizenship void. In respons, Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship in 1925, becoming stateless. He remain stateless until 1932 when he recieved his German citizenship.

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. This prompted Augspurg and Heymann to not return to Germany after a winter trip, since their feared repraisals, having been such vocal opponents to Adolf Hitler. Eventually, all their property in Germany was confiscated by the Nazi regime and all written material in their home disappeared.

At first, Augspurg and Heymann lived in Switzerland, but they eventually moved to South America. When they returned to Europe, they settled in Switzerland again. After Heymann’s death in 1943, Augspurg only lived for a few more months before dying on 20 December that same year, 86 years old. Both women are burried at the Fliuntern Cemetary in Zürich.

This article was last updated on: December 3, 2020